The Poisons Behind Polio

Arsenic, Mercury, Lead Arsenate, and DDT

The polio vaccine is regarded as the gold standard of vaccines. Thus, when the mRNA vaccines are criticized, one often hears the denunciation met with some variation of “But what about polio?” And remember how Fauci raised the polio flag when he was asked why social media was allowing anti-vaxxers to speak:

“We probably would still have smallpox and we probably would still have polio . . . if we had [back then] the kind of false information that’s being spread.”1

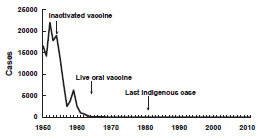

If you’re reading this post, it’s quite likely you already doubt Fauci’s veracity when he declares today’s mRNA vaccines “safe and effective.” Yet you probably believe your high school biology textbook’s account of how the polio vaccine eradicated that dread disease, right? Polio, you learned in 9th grade, is caused by the poliovirus, which was eradicated by the widespread administration of the polio vaccine. For proof of that fact, one need look no further than this chart from the CDC:

As we can see, everybody was dying of polio, then the first polio vaccine was invented, and it instantly started preventing polio. And then an even better polio vaccine was invented and, . . . poof, no more polio.

Hmmm, are you sure you trust any CDC chart these days? What if I were to mention a few problems with the official explanation of how polio was wiped out? For starters, let’s see what happens if we expand the timeline of the CDC’s polio chart:

What was it that occurred in 1916? If we’re going to give the polio vaccine credit for the decline in the 1950s and ’60s, how do we explain the even larger decline following the 1916 spike?

Forrest Maready takes a closer look at polio and answers these questions in his book, The Moth in the Iron Lung, which I highly recommend. While you’re waiting for the print copy you’ve ordered to arrive, check out Maready’s Twitter thread on the subject. In it, you’ll see his convincing case that there is more than one cause of polio. He shows that the environmental heavy-metal poisons administered through medicines and consumed via pesticide-treated fruit crops played a much more significant role than did a poliovirus in causing the paralysis that we associate with polio.

It is difficult for a modern human to understand the ubiquity of mercury, the earth’s most toxic substance (besides plutonium), in the every day life of someone living two hundred years ago. Examine any medical literature of the 1800s and early 1900s and one will not have to look far before seeing mercury-based treatments and medicines; Mercury cyanide, mercuric iodide, mercury benzoate, and mercuric choloride. These were not concoctions sold on the back pages of newspapers by traveling salesman who would clear town as soon as they had your money. These were commercial products produced in laboratories by large companies like Sharpe & Domme and Eli Lilly.2

Throughout the 1800s, Maready tells us, there were occasional cases of what was called infantile paralysis, teething paralysis, and eventually poliomyelitis. The timing of infantile paralysis with teething spawned various theories at the time. But, looking back, it is hard to ignore the role of the “medicine” administered to teething infants.

In the early 1800s, a popular medicine stormed onto the market: Steedman’s Teething Powders. [. . .] Each paper contained around 47 milligrams of mercury chloride powder to be placed on the back of the infant’s tongue and washed down with milk or water. While they knew the mercury could have toxic effects, the drive to clear the infant’s bowels was believed to be so essential to their health as it was thought worth the risk. As such, mercurial medicines were dispensed to infants for nearly any complaint, including the privation of teething. Paralysis is now a known side effect of mercury poisoning.3

Along with medicines containing mercury, people in the 1800s were also exposed to a substance called Paris green.

Paris green was an arsenic-based pigment that [. . .] was tremendously popular and began being used for wallpapers, fabric, toys, and even occasionally, food. [. . .] As safer tints arrived on the market, Paris green began to be sold as a powerful pesticide.4

Though Paris green was toxic, it was not toxic enough to kill the dreaded gypsy moth that was spreading through the Northeastern U.S. in the early 1890s. In response to that insect plague, a chemist developed a more powerful insecticide that combined the arsenic of Paris green with lead. The new lead arsenate was not only more toxic than Paris green but it was also sticky enough to remain on the fruit and vegetation it was applied to, even after a rainfall.5

By 1893, lead arsenate had caused so many cases of “poliomyelitis” in Boston that people began to look for how that “disease” was spreading. In neighboring Vermont, a 1894 outbreak of poliomyelitis killed 18 people and caused paralysis and other serious damage in more than 100 other Vermonters. This event is now recognized as the first outbreak of polio.6 The role of lead arsenate, which “coincidentally” was used on fruit trees and other crops in Vermont, is ignored in the official polio history.

By the late 1800s, many states had passed laws mandating that crops be sprayed with pesticides. Lead arsenate was then added to the “mandated” pesticides list in those states, and by 1914 it was being sprayed on virtually every crop. But just because there were government mandates didn’t mean that state officials took responsibility when children died of arsenic poisoning. Instead, the politicians and bureaucrats were quick to throw the farmers under the proverbial bus for “improper” application of the p̶o̶i̶s̶o̶n̶ pesticide. Meanwhile, some farmers, scientists, and informed citizens began to question whether it was a good idea to coat a large part of the food supply in lead and arsenic.7

If you take a quick peek back at the polio case chart, you may now begin to suspect that the spike in polio cases in 1915-1916 was not a mere coincidence. At the time, however, Koch’s Postulates had taken the scientific and medical world by storm, and it was clear to the Rockefeller Institute and the medical establishment that poliovirus was the sole cause of polio symptoms and the only path forward was to s̶t̶o̶p̶ ̶s̶p̶r̶a̶y̶i̶n̶g̶ ̶p̶o̶i̶s̶o̶n̶ ̶o̶n̶ ̶t̶h̶e̶ ̶f̶o̶o̶d̶ find a poliovirus vaccine!

While the scientists at the Rockefeller Institute in New York City were hard at work d̶e̶v̶e̶l̶o̶p̶i̶n̶g̶ ̶a̶ ̶b̶i̶o̶w̶e̶a̶p̶o̶n̶ researching ways to make the poliovirus more virulent so they could develop a vaccine for it, there was a devastating polio outbreak in many parts of the city. The public health officials responded in the only way public health officials have responded for the last century—by demanding that everyone stay inside and by cancelling summer camps and day trips to the countryside and by closing public swimming pools and bathhouses. These regulations of course impacted only the lower classes; those with means just sent their children as far away from New York City as possible.

The administration of vaccines of various sorts were followed by the nearly immediate onset of poliomyelitis. But doctors naturally did not want to blame their safe and effective mercury or horse-blood injections, so they called this phenomenon “provocation polio” rather than real polio. This still goes on today, but now instead of “provocation polio” the vaccine-induced polio symptoms are called “polio-like illness.”

It was 1935 (not the 1950s) when a polio vaccine was developed by Dr. Maurice Brody of the Rockefeller Institute and given to over 3,000 children. Although the media reports were quite positive, Rockefeller Institute scientists would later admit to seeing cases of polio among the vaccinated children and to quietly shelving the vaccine. Apparently there was still some degree of conscience among the vaccine scientists of that era.8

Another scientist, John Kolmer, developed a supposed polio vaccine in 1935 and distributed it widely via physicians in 36 states. But this experiment proved deadly—in fact, too deadly to totally cover up, as many of the children who received the Kolmer vaccine died.9 Isn’t it interesting how little the 1935 polio vaccines are mentioned these days? Strangely, the CDC doesn’t even bother including 1935 on its polio chart.

While the vaccines of that era are admitted failures, the 1930s saw a sharp rise in opposition to the use of lead arsenate. European countries had been demanding lower levels of pesticides on apples and other crops shipped to them across the Atlantic for years, and now the awareness of lead arsenate’s toxicity was finally receiving widespread attention domestically as well. The pest problem still had to be solved, though, so the search for a “better” option than lead arsenate finally led to a synthetic compound first developed in 1874: DDT.10

DDT was mainly used on US troops in the Pacific theater during WWII. Not surprisingly, polio commonly afflicted US troops whose uniforms were treated with DDT and whose bodies were sprayed with DDT to protect them from mosquitoes. This “virus,” for some reason, did not seem to affect the native populations of the Philippines, China, and other Asian countries.11

After WWII, DDT began to be sprayed liberally all over the United States. It was sprayed from airplanes, trucks, and from bottles that parents applied directly on their children. Not only did polio cases skyrocket, but a whole new “virus” called “disease X” sickened an estimated 10% of the population in Los Angeles as well as residents of Austin, Texas, and Arizona, and even as far away as Pennsylvania.12

Perhaps because the usage of DDT went from near zero to near ubiquitous in such a short time, the accompanying outbreaks of polio and disease X raised the suspicion of doctors, journalists, and others that DDT might not be as safe as initially advertised.

Articles appeared in papers throughout the world claiming “Virus X caused by DDT Poisoning.” A Pulitzer Prize-winning author named Louis Bromfield jumped on board and began promulgating the theory that DDT—and possibly lead arsenate—might have been contributing to Virus X and infantile paralysis.13

The FDA insisted the claim that DDT was unsafe arose from an outrageous conspiracy theory (okay, they didn’t use that CIA-weaponized term in those days):

Statements that DDT is responsible for causing the so-called “virus X disease” in man and X-disease of cattle are totally without foundation. [. . .] Both of these diseases were recognized before the use of DDT as an insecticide.14

By the early 1950s, the tide was turning against DDT. Products were advertised as DDT-free, mothers no longer sprayed DDT on their kids and on the lunch their kids brought to school, and children were discouraged from playing in clouds of DDT spray.15

It wasn’t just DDT that was losing favor, however. Mercury medicine, too, was becoming less trusted.

Even Steedman’s Teething Powder, the mercuric medicine trusted for over 140 years [. . .] announced it would begin using a new formula, this time with the mercury.16

The decreasing usage of DDT certainly correlates neatly with the decline in new cases of polio, doesn’t it? Is it possible that the sharp descent of polio cases spurred the government and medical establishment to finally roll out another polio vaccine after 20 years in order to claim victory? In the war on germs, the only thing worse than losing is winning without being able to explain why.

https://news.yahoo.com/fauci-us-might-still-polio-204319871.html

“The Moth in the Iron Lung” pg 37

Ibid 37-38

Ibid 52

Ibid 61, 62

Ibid 70

Ibid 104-105

Ibid 204-205

Ibid 205

Ibid 212-213

Ibid 214-215

Ibid 222-223

Ibid 225

Ibid 226

Ibid 236

Ibid 236